By Liza Roberts • Photographs by Trey Thomas

Last August, when the quilt artist George Snyder III and his wife, Jill, drove 16 hours straight from their home in Ayden, North Carolina, to the New Hampshire home of the filmmaker Ken Burns, it was a dream come true, and not just because they’re fans of his documentaries. The couple went because Burns is also one of America’s great quilt collectors, and he wanted one of George’s rare, hand-sewn quilts for his historic collection.

“It was such an honor,” Snyder recalls. “He was so excited and enthusiastic about receiving the quilt, and said there was no male quilter represented in his collection. He had never met a male quilter.”

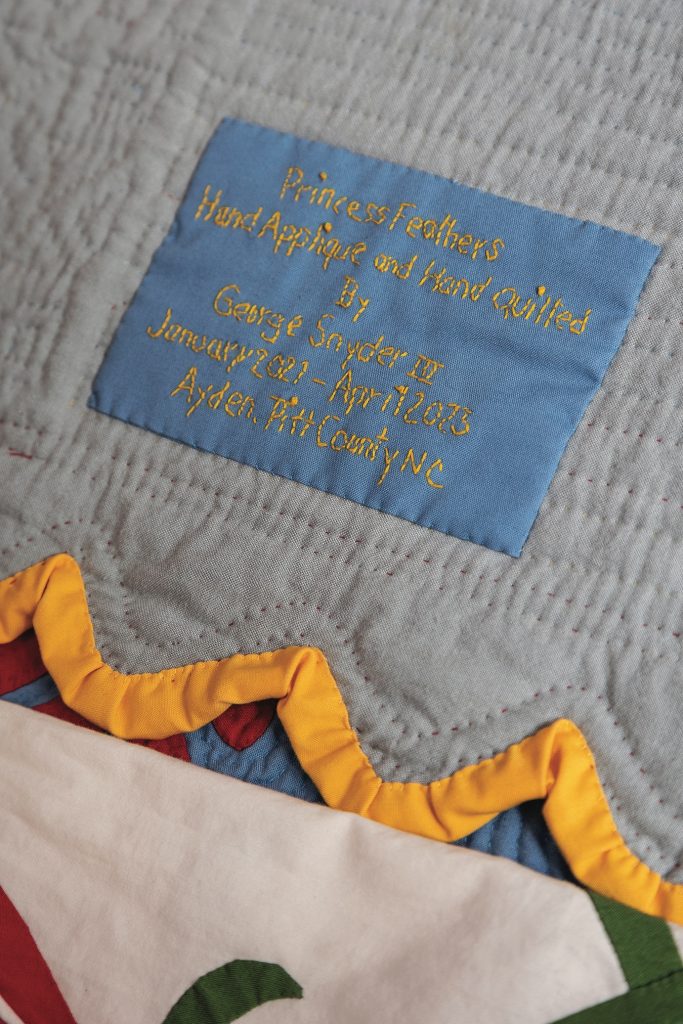

Most people have never met a male quilter. But Snyder’s more important distinction is that he sews his quilts — pieces them together, appliques them and quilts them — entirely by hand, the way they were made hundreds of years ago. Stitch by tiny, meticulous stitch, he replicates early American quilts in exactly the way they were made to begin with. It’s a painstaking, nearly extinct process. Which is exactly why he does it.

“My main focus is on preserving the history and the tradition of hand quilting,” Snyder says. “Even the machine quilters recognize that a hand-quilted quilt feels and looks different. It tells so much about a community and a person.”

The eastern North Carolina quilting community agrees. Snyder’s one-man show at Greenville’s Emerge Gallery in 2024 was hugely successful, and the Greenville Museum of Art plans to honor him with its Nancy Monroe Artist of the Year award in February 2026. “His work is so beautiful,” says Trista Reis Porter, the museum’s director, who is committed to celebrating traditional art forms including textiles. “You don’t find a lot of quilters making quilts by hand, and he’s so tuned into the history of quilts and quilt patterns.”

Snyder feels the way Burns does about the art form: “As a collector,” Burns told the International Quilt Museum when they mounted a major exhibition of his quilts in 2018, “I’m looking for something that reflects my country back at me. Quilts rearrange my molecules when I look at them. There’s an enormous satisfaction in having them close by. I’m not a materialist. There are too many things in the world, and we know that the best things in life aren’t things. Yet there are a few things that remind me of the bigger picture. We live in a rational world. One and one always equals two. That’s OK, but we actually want — in our faith, in our families, in our friendships, in our love, in our art — for one and one to equal three. And quilts do that for me.”

The Snyder quilt Burns chose for his collection is blue cotton in a pattern called Flocks of Geese, hand-quilted in a Double Baptist Fan pattern. It is 8 feet long and almost 5½ feet wide. As the Snyders presented the quilt and toured Burns’ house and the barn where he works in the town of Walpole, they were awed by the company Snyder’s quilt would keep. Fine antique quilts covered every inch: the walls, the beds, the sofas and cupboards. They hung off ladders and were displayed as art.

While this was all undeniably impressive, it also felt like home to the Snyders, whose 1929 brick Colonial in downtown Ayden is also full of quilts, also steeped in history, and also situated in a small, historic, close-knit town.

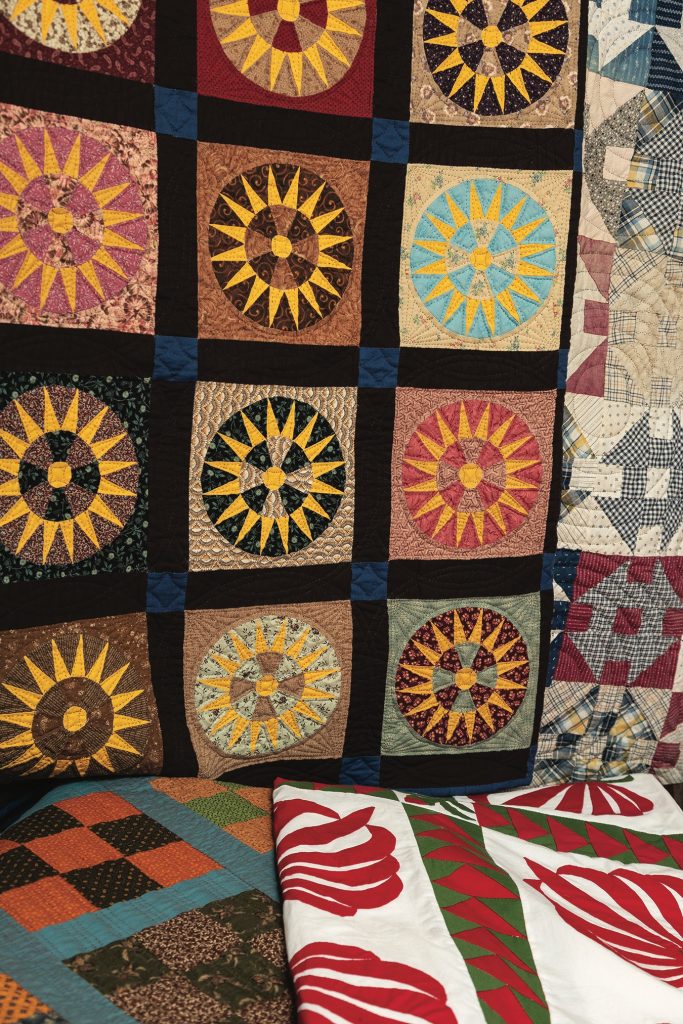

Clifton Ash is the name of the antiques-filled house where Snyder sews quilts at his long dining room table as classical music plays. Oil painted portraits of his forebears, and of Jill’s, oversee his work as he makes quilts that replicate hundreds-year-old patterns, techniques and styles. Historic quilts from the American South, in particular those from North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia in the 1800s, inspire him most.

The patterns and styles they showcase give his speech a lyrical flourish: “Churn Dash,” he says offhandedly, or “Monkey Wrench.” There’s “Cotton Boll,” and there’s “Fence Rails.” There’s “Welsh Strip” and “Pinwheel and Spikes.” Some seem obvious to him, like “Your Regular Nine Patch.” Others evoke simple images and pleasures: “Sugarloaf,” “Orange Peel,” “Butterflies,” “Oak Leaf,” or the more expansive “Grandmother’s Flower Garden.”

Examples of these can be found upstairs and down at Clifton Ash. Some are historic, some are made by Snyder. All capture the spirit of a slower, pre-industrial age. Until the sewing machine was patented by Isaac Singer in 1851, and became common in middle class homes in the 1860s, there was no other way.

Working in, and respecting, the old ways is something George and Jill Snyder met doing and have always done. The art studio beside their house — where George still paints murals, furniture and home decor — is where you’ll find a beautiful old horse carriage, a reminder of the work that brought them together more than 30 years ago in the Belgium workshop of a top European horse harness maker, one whose techniques hadn’t changed in hundreds of years.

The past is present in their conversation as well. George’s family’s American history begins in pre-Civil War Virginia; his North Carolina history traces back to his great-grandfather, J. Luther Snyder, who moved to the state in 1904, becoming its first and leading Coca-Cola bottler. His Blowing Rock home, Chetola, was the site of family summers until the 1980s, and eventually became the famed Blowing Rock resort.

Jill, who was born in the British Midlands and grew up in Gloucestershire, had a long career as a horsewoman that also brought her in touch with living history. Her work teaching carriage driving at the Sandringham Estate introduced her to HRH Prince Philip, with whom she developed a friendship that continued even after she moved to the United States. Their regular correspondence lasted decades, and she keeps more than 70 letters she received from Philip over the years in a special album.

So maybe it’s not such a surprise that George was so quickly drawn to this old, demanding, unchanged form of art. He fell in love with hand quilting while recovering from back surgery in 2018 and “needed something to do with my hands.” Jill unearthed a partial quilt he’d begun 30 years earlier with the help of a nanny — he loved needlework as a child and younger man but had left it behind — and she put it in front of him. “Here,” Jill said. “Finish this.”

“So,” he says, “I finished it. Then I entered it into a quilt show in Greenville and won Best in Show.” That surprised him, because the style of the quilt, known as “Cathedral Window” (a three-dimensional compilation of small, folded fabric squares that resemble stained glass), was so unusual.

The experience ignited something in him. It wasn’t long before Snyder signed up for a beginner’s quilting class at the church across the street from his house, and a quick 10 weeks later, “I’d made my first quilt from start to finish, a little nine-patch.”

“Once I learned that,” he says, “I just took off.” The next one he made was a replica of an 1841 Mississippi quilt in a “Pomegranate” pattern. Soon, he was quilting full time: studying historic quilts, collecting them, repairing them, replicating them.

The Ayden community has clearly rallied around Snyder and his work, as a walk around town on a sunny weekday morning makes clear.

A few blocks from his house is the Town of Ayden Museum, where his first “little nine-patch” is on display. Andrea Norris, the president of the Ayden Historical and Arts Society, and Phil Barth, its artistic director, greet him effusively, eager to talk about his work. Barth, an accomplished artist in his own right, painted the remarkable mural on the museum’s exterior depicting the historic Ayden train depot in 1890. A few blocks farther, Snyder can’t order a chicken salad sandwich at Gwendy’s Cafe & Bakery without people stopping him to ask about his quilts.

Back at home, Snyder is working on a replica of an 1800s quilt from Caswell County that he saw at the North Carolina Museum of History, a red and green applique quilt he realized had been owned by a family he knew. “This will be my personal cherry on top,” he says.

He’s also got a major community quilt project underway, an 18th century-style, all white, “whole cloth quilt” he’s making with a group of seven women every Thursday and Saturday at the church across the street. It’s 7 feet square, stretched out on a frame, and together they hand sew pieces that will be stuffed with wool to form two-dimensional relief designs. Their goal is to complete it by July 4, 2026, to honor America’s 250th birthday. After that, he’ll donate it to the Town of Ayden Museum.

“I’m really trying to promote the art and craft of hand quilting with this one,” he says. “And it’s a way to pull the community together.”

It’s also a way to share an art form he loves dearly, one he describes as a passion. “A quilt that’s hand-quilted feels different,” he says. “It presents an aura. The person who made it is thinking of (its meaning) with every stitch. So that quilt is saturated with positive thoughts, love, tenderness, whatever you want to call it. That quilt is just saturated. You can feel it just by touching it.”